Converting pre-tax dollars from an individual retirement account (IRA) to Roth dollars held in a Roth IRA is a relatively popular strategy known as a Roth conversion. James Chapman discusses the rules that investors are subject to when carrying out a Roth conversion, as well as certain variables that can make the strategy more or less appealing, in Strategies for Managing Retirement Distributions – click this link to access the full article.

In the context of Roth conversions, the list of factors that can materially impact the performance of a Roth conversion strategy is extensive and often overwhelming to investors, making the decision of whether to carry out such a strategy even more complicated. At the forefront of said considerations are variations in tax rates.

The Rule of Thumb

The federal government deploys several types of incentives in order to encourage behaviors, investments, and economic activities. Among said incentives is the option to save for retirement on a tax-deferred or tax-free basis by investing in tax-advantaged retirement accounts, such as employer-sponsored 401(k)s and traditional IRAs (amongst others). Tax-advantaged retirement accounts can present the opportunity to convert pre-tax dollars to Roth dollars.

The simplicity of this approach is quickly muddled in efforts to respond to the following question: What is the lowest tax rate you can reasonably expect to pay when taking money out of your pre-tax retirement account? Investors often seek to address questions of this sort without realizing the emergence of an entirely new discussion regarding estate planning. Just as variations in income at different phases of life present differentials in marginal tax rates, so too do changes in tax filing status. While Roth conversions can be used to accelerate income to lower an investor’s tax bill over time, they can also be used as an estate planning tool to help protect against an unexpected change in filing status, commonly referred to as the “widow tax penalty”.

The Concept That the Rule of Thumb Often Overshadows

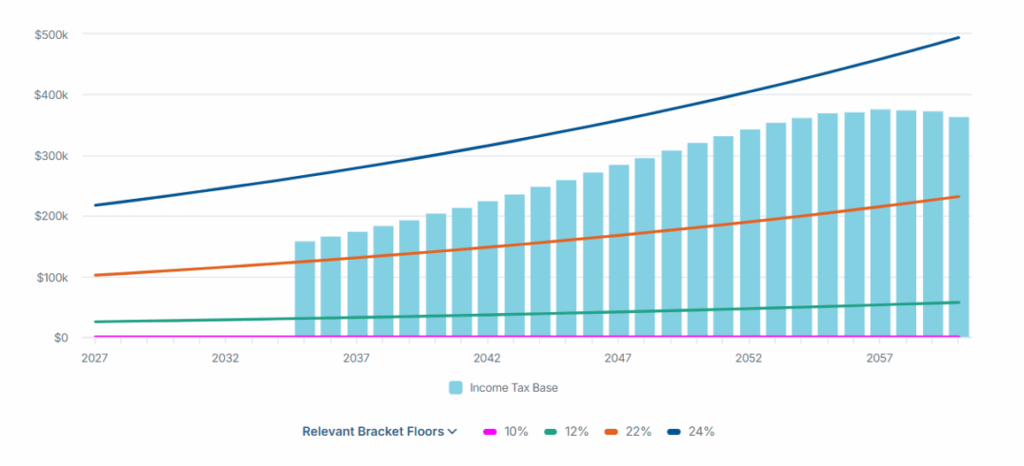

The widow tax penalty refers to the transition from the married filing joint (MFJ) status to the less favorable, single filing status that occurs after a spouse passes away.* Take, for example, a married couple consisting of two individuals who are equal in age and who have just retired at the age of 65. After consulting with their financial advisor, it was brought to their attention that the large balance in Spouse A’s traditional IRA is projected to push them into the 22% marginal tax bracket once Spouse A begins taking required minimum distributions (RMD), as illustrated in Figure 1, below. Figure 1 depicts blue, vertical bars that represent the couple’s income tax base, along with horizontal lines that represent the relevant tax brackets.

*Carlson, B. (2020, December 14). The onerous widow(er)’s penalty tax and how to avoid it. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bobcarlson/2020/12/21/the-onerous-widowers-penalty-tax-and-how-to-avoid-it/

Figure 1 – RMDs Forecast

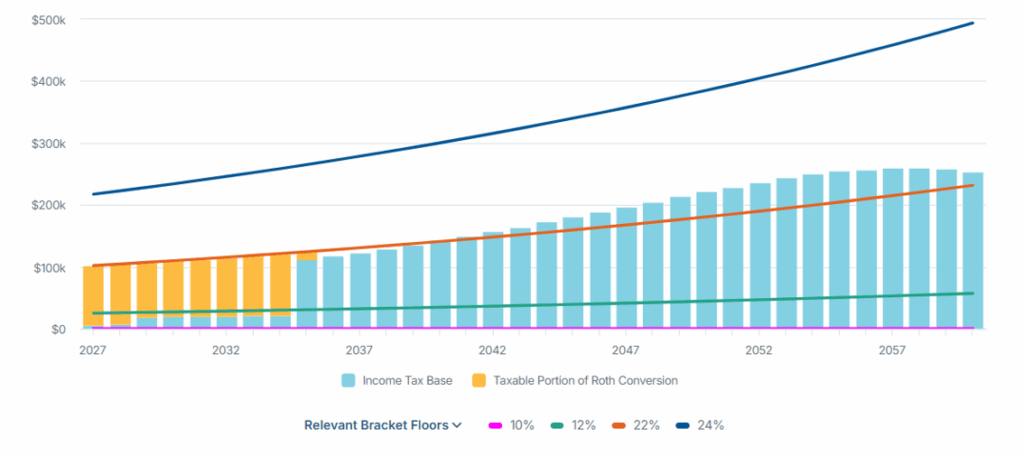

Continuing the example, their financial advisor projected a strategy that consisted of annual Roth conversions in the years leading up to the age that Spouse A would be required to begin taking RMDs (referred to as the “required beginning date” or “RBD”). The annual Roth conversions are structured so that the couple’s taxable income fills the 12% marginal tax bracket without spilling into the 22% bracket, as illustrated in Figure 2, below. In doing so, projections reflect the couple remaining in the 12% bracket through 2040 and reduced exposure to the 22% bracket thereafter. Figure 2 depicts the same items as Figure 1, along with the addition of orange, vertical bars that represent the couple’s taxable income generated from annual Roth conversions.

Figure 2 – RMD Forecast with Roth Conversions

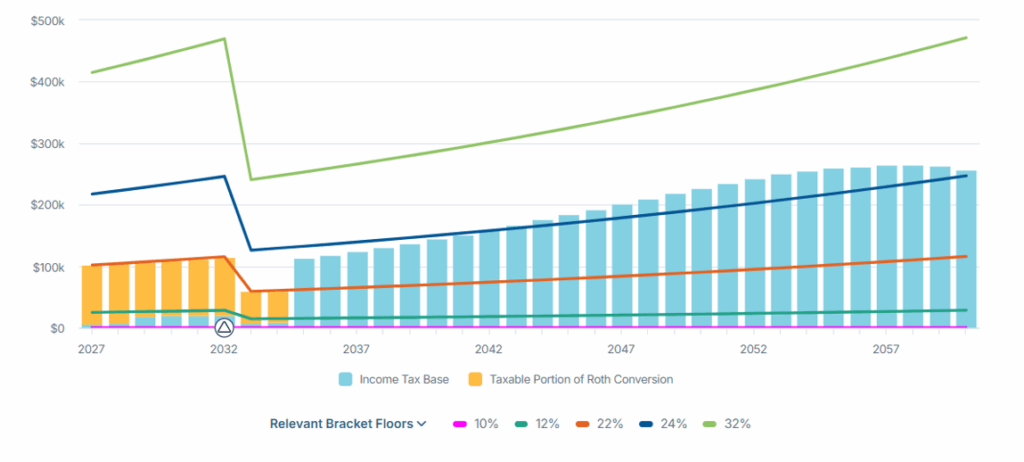

To gauge the couple’s tax exposure under different scenarios, the financial advisor reruns the projections shown in Figures 1 and 2, assuming Spouse A passes away in 2032 at age 72. This exercise highlights the potential impact of the widow tax penalty with and without Roth conversions, as illustrated in Figures 3 and 4, below.

Figure 3 – RMD Forecast with Spouse A Passing at the Age of 72

Figure 4 shows the acceleration of income under the Roth conversion strategy, along with taxes being paid at MFJ tax rates. The result is the avoidance of heightened tax exposure under the single-filer brackets in the event of a sudden death.

Figure 4 – RMD Forecast with Roth Conversions and Spouse A Passing at the Age of 72

Ultimately, protecting a surviving spouse from the widow tax penalty is one of the many instances where Roth conversions can extend beyond chasing a lower tax bracket. Other applications that were not discussed in this article include enhancing long-term flexibility, risk management, legacy planning, and more. If you would like to learn more about how these strategies might apply to your specific case, please get in touch with your advisor or the Clearwater Capital Planning team.

Figures 1-4 reflect a hypothetical case and should not be considered tax or legal advice. For more information on tax-advantaged retirement accounts, visit irs.gov.

20251201 – 3

John E. Chapman Chief Executive Officer

John E. Chapman Chief Executive Officer